U.S. Marine Corps Combined Action Program

August 1, 1965

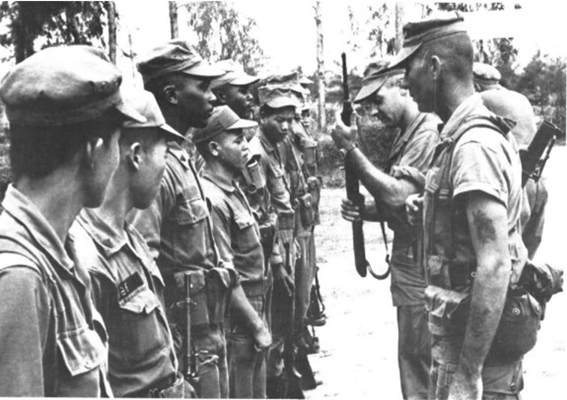

The Marine Corps inaugurates the Marine Combined Action Platoon Program. The program is part of the U.S. Marine Corps’ pacification efforts in northern South Vietnam, the military region known as I Corps. It deploys enlisted men and noncommissioned officers, organized into Combined Action Platoons (CAPs), to live in rural villages and attempt to gain the trust and support of villagers, encouraging them to provide intelligence on local insurgency activities. CAPs also train local militiamen, help with local construction and repair projects, and provide medical services to villagers. The CAP program’s overarching aim is to deprive the Viet Cong of their rural bases and support.1

In 1967, the Marine Corps establishes a formal two-week school to train CAP Marines for the cultural, military, and political complexities they encounter in Vietnamese villages. The CAP program peaks in late 1969 with 114 active CAPs (approximately 1,900 Marines) in the field, living in about 20 percent of the villages in I Corps. CAPs are slowly deactivated beginning in 1970, in conjunction with the general American withdrawal from Vietnam, and the program permanently ends in May 1971. While the CAP program leads to relative successes at particular times and in particular places, overall it does not achieve its long-term goals.

Since the end of the war, some historians have posited that the Marine Corps’ Combined Action Platoons would have been a better counterinsurgency tactic for the United States to have pursued throughout South Vietnam during the war. Inspired by the Marine Corps’ experiences with unconventional warfare in U.S. interventions in Latin America, the CAPs paired a platoon of Marines with a South Vietnamese militia unit and tasked the group with protecting a village. By living together in a village, CAP Marines and Vietnamese civilians gained an intimate knowledge of one another. Contact with the villagers provided the Marines with intelligence on insurgent activities, while the South Vietnamese obtained firepower, training, and trust from the constant American presence.

Proponents of this system argue that the CAPs, though deployed sparingly, won hearts and minds and delivered greater security to the countryside. These scholars assume that a system such as the Marine Corps’ CAPs would have been far more effective at counterinsurgency than the Army’s search and destroy tactics. Some who disagree, however, insist that Marine commanders never made more than a token effort at CAPs: the Marine Corps devoted a very small proportion of its total manpower to the program; the Marines’ presence in the village never strengthened South Vietnamese militias to the point where they could defend themselves without American assistance; and the Marine Corps’ leadership, frustrated with the defensive posture this program required, abandoned CAPs in favor of “going Army,” or seeking to destroy the enemy in battle with superior mobility and firepower.

Cable, Larry E. Conflict of Myths: The Development of American Counterinsurgency Doctrine in the Vietnam War. New York: New York University Press, 1986.

Hess, Gary R. Vietnam: Explaining America’s Lost War. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2009.

Lewy, Guenter. America in Vietnam. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

Peterson, Michael E. The Combined Action Platoons: The U. S. Marines’ Other War in Vietnam. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1989.